The First Stewards of Yellowstone: Indigenous Peoples and Their Deep Connection to the Land

Blog by YW Naturalist Parker N.

Before Yellowstone became famous as the world’s first national park in 1872, it was a home and hunting ground for Native American tribes who occasionally lived, and regularly traveled through, for thousands of years. While many people think of Yellowstone as a “pristine wilderness,” untouched before it was protected, the truth is very different. For countless generations, Indigenous peoples hunted, gathered, traded, and held ceremonies on this land. They knew it intimately and cared for it in ways modern conservation is only beginning to understand.

Archaeologists have found evidence that people have lived in the Yellowstone area for at least 11,000 years. This evidence includes ancient tools, campsites, and even stone points made from Yellowstone’s obsidian. Local tribes across North America traded this sharp volcanic glass.

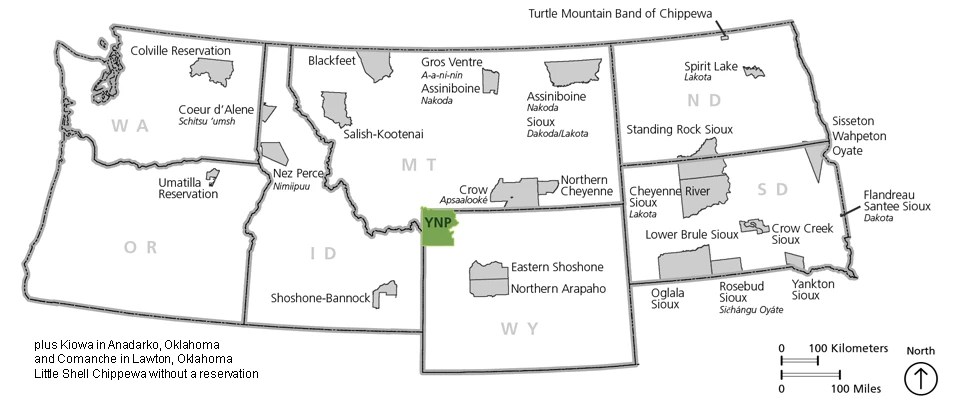

More than two dozen tribes have historical and cultural connections to Yellowstone, including the Shoshone, Bannock, Crow, Blackfeet, Nez Perce, Lakota, and many others. Some tribes passed through the area seasonally to hunt or gather food. At the same time, one, the Tukudika or “Sheepeaters”, occasionally lived there year-round. These Indigenous groups knew how to live in harmony with the land, following animal migrations, collecting plants, and fishing in Yellowstone’s rivers and lakes.

One of the best-known groups in the Yellowstone area today are the Tukudika, commonly called the “Sheepeaters”, a name given to them by outsiders because they relied on bighorn sheep. These people lived in the high country–occasionally year-round if a mild winter presented itself. This was something early European-Americans didn’t believe was possible.

The Tukudika were expert hunters and craftspeople. They made detailed traps and tools from local materials, including obsidian from Yellowstone’s cliffs. Their way of life shows how well they adapted to and understood the land, contrary to early myths that Indigenous people avoided Yellowstone because of its geothermal activity. For many Native American groups, Yellowstone wasn’t just a place to survive; it was a sacred landscape full of meaning. The geysers, hot springs, rivers, and animals all played roles in spiritual stories and cultural traditions. These stories and traditions often revolved around the creation of the land, the spirits that inhabited it, and the lessons it taught about living in harmony with nature.

Sheepeater bow making materials acquired from big horn sheep ram horns. The horns were made pliable by soaking them in area hot springs. Photo courtesy of Jim Peaco, NPS photo library.

Obsidian Cliff, for example, was more than just a valuable place to gather stone for tools. It also had spiritual value. Some tribes saw hot springs and geysers as powerful spiritual places or connections to other worlds, and one tribe, the Kiowa, believed the churning waters of Dragon’s Mouth at Mud Volcano explained their creation. The land was alive in ways that went far beyond what early park founders understood.

The Kiowa people believe their creation was borne out of Dragon’s Mouth spring in Yellowstone’s Mud Volcano thermal area. Photo by Tyrene Riedl

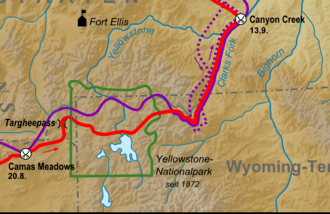

When Yellowstone became a national park in 1872, it was celebrated as a bold move to preserve nature. But it also led to the forced removal of the very people who had lived there the longest. Early park officials and government leaders claimed that Native Americans were afraid of geysers and avoided the area, which wasn’t true. That myth made it easier to push tribes out and keep them from returning. Some tribes, like the Nez Perce, still passed through Yellowstone even after the park was established. In 1877, during their flight from the U.S. Army, a group of Nez Perce traveled through the park as part of their long journey toward Canada. Their path is now recognized as a significant historic route and part of the park’s complex history.

This map outlines the flight of the Nez Perce (red) from their native lands in NE Oregon as they try to outrun the US Army (purple) in an attempt to get to Canada. The Army was planning to relocate the Nez Perce to reservation land. The Nez Perce made in to within 40 miles of Canada before surrendering near the Bear Paw Mountains on October 5, 1877.

Today, the National Park Service is working more closely with tribes to honor Yellowstone’s Indigenous history. The park now recognizes 27 tribal nations with ties to the land. These partnerships involve collaborative research, interpretation, and management of the park. They are helping to tell a fuller story, one that includes Native voices and experiences. Visitors can now learn about Native history at park exhibits and through educational programs. Some tribes are also regaining access to sacred sites and helping to guide how Yellowstone is managed and interpreted. It’s an essential step toward recognizing that these lands were never ’empty’ or ‘wild’ in the way early park creators believed.

Yellowstone Revealed: Resiliency of the People was an art installation in Gardiner, MT at Yellowstone’s North Entrance. 2022 Yellowstone celebrated it’s sesquicentennial with a focus on recognizing the long history of the areas original inhabitants.

Yellowstone is known around the world for its geysers, wildlife, and stunning landscapes. But long before it became a park, it was home to Indigenous peoples who understood, respected, and cared for the land in powerful ways. As we enjoy Yellowstone today, it’s worth remembering and honoring those original stewards and recognizing that their connection to the land is still very much alive.

To learn more about Parker, and the entire Yellowstone Wild team, check out our About Us page